Nation-states are odd things. They are not really “tribes”, and are “more” than cities. But, perhaps insensibly, the mass of people today self-identify with one nation or another. Things have been this way since long before the Egyptians duked it out with the Hittites at Kadesh.

But sometimes…things go sideways. Really sideways.

On December 26th, while most of the world was still digesting Christmas leftovers, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did something that might prove to be the most consequential geopolitical act since 1945: Israel became the first nation to formally recognize the Republic of Somaliland as an independent state.

Somaliland has been seeking international recognition since 1991 – and recently tried to entice the United States with a similar offer of basing rights as they offered to Israel – but has been rebuffed by the “international community” at every turn…until now.

This act by Israel immediately set off hysterical outcries throughout the United Nations (but not from Israel’s closest regional allies, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), note), with the Security Council calling an emergency session on the matter. However, complaints were short-circuited by Tammy Bruce, the United States’ Ambassador to the UN, who pointed out that Israel’s action in recognizing Somaliland was in no way different than the UN’s own actions in recognizing a state – Palestine, in 2012 – that has a far better claim to “legitimacy” than either Palestine or Somalia itself.

If your reaction is “So what? Some breakaway African territory got recognized by Israel — big deal,” then you’re missing what just happened. This isn’t about Somaliland. This is about the deliberate destruction of the international order that’s governed the planet since World War II ended…and may be the death-knell for the 400-year old Treaty of Westphalia – which matters a very great deal.

What Westphalia Is, and Why It Matters

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) established the principle that sovereign states have exclusive authority over their territory and that external powers shouldn’t interfere in their internal affairs. After 1945, this was modified: the United Nations system added the idea that existing borders are sacrosanct and territorial integrity must be preserved. In practice, this meant that no matter how artificial, dysfunctional, or oppressive a state might be, its borders were frozen in place by “international consensus.”

This system has a name in international law — the “constitutive theory” of statehood — which holds that you’re only a legitimate state when other states recognize you. It supposedly replaced the older Montevideo Convention standard (but see below…), which holds that you’re a state if you have: a permanent population, a defined territory, a functioning government, and the capacity to conduct foreign relations. “Recognition” just acknowledged an existing fact; it didn’t create statehood.

The problem with constitutive theory that should be obvious after about sixty seconds of thought is: who recognized the first state? The whole concept is circular logic masquerading as international law.

The Hidden Crowbar

One of the leading opponents of Israel’s move – Slovenia – complained that it was a violation of a member-state’s sovereign territorial integrity…which is a very rich and ironic take on the subject, given that the former Yugoslavian state’s existence as a sovereign nation was confirmed by the 1991 Badinter Arbitration Commission, which – by the UN’s own rules – openly and nakedly violated Yugoslavia’s sovereign territorial claims.

Why is this important? Because of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States.

Signed in 1933, and ratified into law in the United States in 1934, this international legal agreement defines precisely what is required for a state to be a state, namely: a) a permanent population; b) a defined territory; c) government; and d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.

But the Convention goes on to use significant specific language. It is worth quoting Article 3 in full:

“The political existence of the state is independent of recognition by the other states. Even before recognition the state has the right to defend its integrity and independence, to provide for its conservation and prosperity, and consequently to organize itself as it sees fit, to legislate upon its interests, administer its services, and to define the jurisdiction and competence of its courts. The exercise of these rights has no other limitation than the exercise of the rights of other states according to international law.”

This is seriously explosive stuff. Re-read that as many times as it takes, if there is an issue with understanding it.

Now, this might be seen as a simple artifact of political maneuvering, except that when Yugoslavia disintegrated in 1991 – which created Slovenia from that state’s remains, among others – the United Nations formed the Badinter Arbitration Commission to determine the future of the region. And, in deciding that the components of the former Yugoslavia were in fact independent nations, the Commission – while not directly citing the Montevideo Convention, even though no state involved had attended or signed it, cited all of its core principles – thus confirmed the Convention as a valid component of international law.

This is the actual basis for the UN recognizing Palestine, because Palestine is as much a “breakaway” part of Israel as Somaliland is of Somalia.

Why Somalia Matters (And Doesn’t)

Somalia has been a failed state since 1991. Somaliland — the former British protectorate portion of the region — declared independence that same year and has maintained effective self-governance, relative stability, and functional institutions for the last 34 years. By any objective measure, including using Montevideo criteria, Somaliland is more of a “real state” than Somalia, itself, which can barely control its own capital.

But under the post-1945 system, Somalia’s non-existent territorial integrity trumps Somaliland’s actual effective and long-standing peaceful and successful governance. Why? Because the “international community” decided so, and because African nations fear that allowing ethnic self-determination will open a Pandora’s box. Nigeria’s strident condemnation of Israel’s move isn’t about solidarity with Somalia — it’s about Biafra and the nightmare that their own artificial borders might be questioned.

The Real Game: Netanyahu vs. The World

Benjamin Netanyahu isn’t stupid, and he’s not doing this for humanitarian reasons. Israel has spent decades being targeted by the UN system, the International Criminal Court, and the entire apparatus of “international law” being wielded as a weapon by nations that want to delegitimize the Jewish state’s existence. In a very real way, the only component missing is red white and black swastika armbands.

By recognizing Somaliland, Netanyahu is making a declarative statement, in effect:

Effective control and governance create legitimacy, not UN votes or ‘international consensus.’ We’re reverting to the Montevideo protocol, exclusively. Israel exists because we hold a defined territory and govern it effectively — in the same way as Somaliland. You don’t get to vote us out of existence.

This isn’t about Somaliland. It’s about destroying the gatekeeping power of international institutions that have become weapons against Israeli sovereignty. And Netanyahu is using the Trump administration’s transactional indifference to global norms as cover to reshape the fundamental rules.

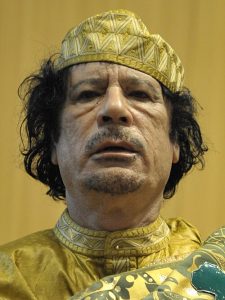

Qaddafi Called It (And Paid For It)

In 2009, Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi gave a rambling speech at the UN where he called the Security Council the “Terror Council,” tore up a page of the UN Charter, and accused the entire system of being neo-colonial power dressed up as international law. He was dismissed as a ranting dictator.

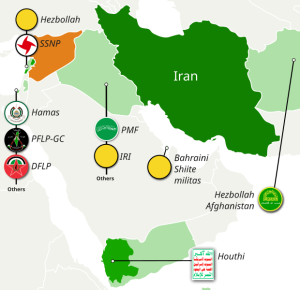

Two years later, NATO — operating under a UN resolution — regime-changed him, turning Libya from Africa’s highest HDI state into a failed state with open-air slave markets. Qaddafi had correctly identified that the post-1945 system was “political feudalism” where five permanent Security Council members could do whatever they wanted while smaller nations faced “consequences” for trying the same actions.

Muammar Qaddafi was a vile individual…but he was not wrong. And they killed him for saying it out loud.

The Cascade Effect

If this precedent holds, the implications are explosive:

- Catalonia’s independence movement gains legal ammunition against Spain and the EU

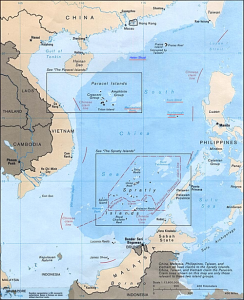

- Taiwan’s status becomes purely about effective governance, not Beijing’s claims

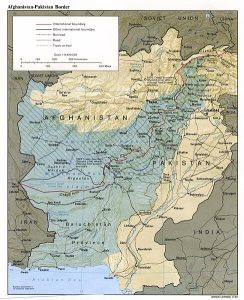

- Kurdistan becomes viable if they can maintain control and get recognition

- Every artificial post-colonial border in Africa and the Middle East becomes reviseable

- Texas…well, the Republic of Texas has serious historical precedent

The African Union, Egypt, Turkey, and Nigeria aren’t panicking because they care about Somalia’s feelings. They’re panicking because most of their borders are artificial lines drawn by European colonial powers that trapped rival ethnic groups together and split coherent peoples apart. Sykes-Picot and the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference created states, not nations. The post-1945 order then froze these arrangements and declared them permanent.

Netanyahu just said: No, they’re not.

Does This Actually Make Things Worse?

Ten years ago, I’d have predicted this would cause a global bloodbath. But would it really? Pre-1945 wars were generally frequent but bounded: limited objectives, clear territorial stakes. Post-1945, we’ve had continuous conflict: Korea, Vietnam, endless Middle East wars, proxy conflicts across Africa and Latin America, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya. The UN system didn’t prevent wars; it just made them illegitimate, forcing them to become covert, proxy-based, or justified through elaborate legal fictions.

We traded occasional large wars for permanent medium-intensity conflict. That might actually be the worse deal.

If destroying the constitutive theory allows organic nations to form based on actual cultural and historical coherence rather than colonial mapmaking, the initial instability might be worth it for long-term viability.

The Bottom Line

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland isn’t about Red Sea access or Ethiopian port deals, although those certainly matter. It’s about one simple proposition: The post-World War II international order, as currently administered, is illegitimate and they’re not playing by those rules anymore.

And it’s the sole fault of the United Nations itself, as their 2012 recognition of the wholly non-existent and non-governed “state of Palestine” handed the United States and Israel all the excuse they needed to unilaterally recognize Somaliland.

Whether you think that’s catastrophic or overdue depends entirely on whether you believe the current system has been preventing conflict or perpetuating it (hint: it’s the latter). But either way, what happened on December 26th of 2025 in Jerusalem is going to reshape the world map in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The post-1945 era might have just ended. Most people haven’t noticed yet.

But they will.