Electricity if the foundation of modern society. Many people wistfully ponder the idea of living permanently in the wilderness, the old “back to Nature” idea. The fact is, most people – at least in the West – are going to survive in the wild for longer than a week. Electricity is what allows you to read this, and not simply because the immediate of an internet connection: electricity is fundamental to the industrial processes that made the device you are reading this on.

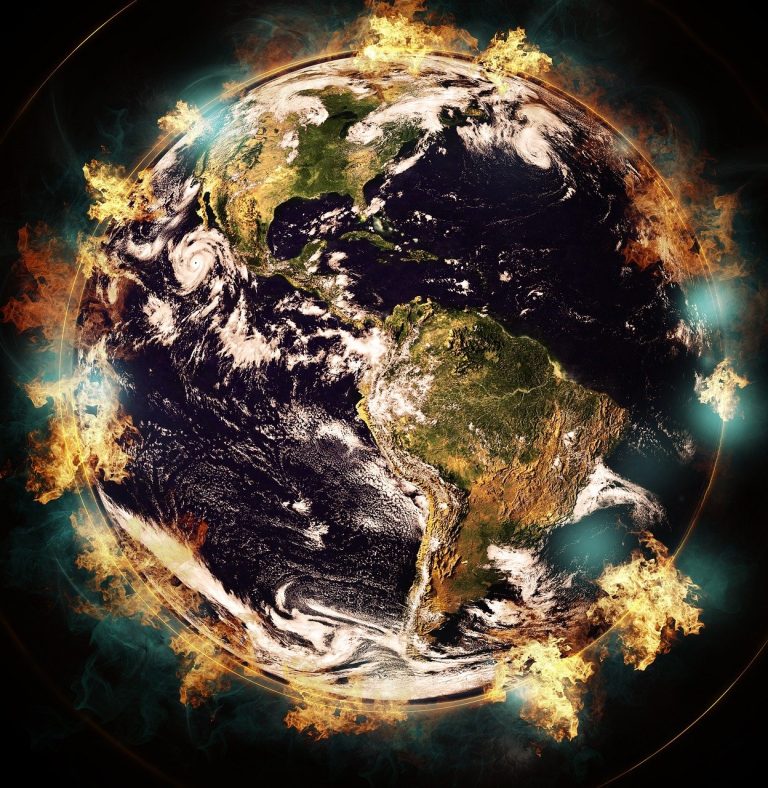

America’s electrical grid represents both the backbone of modern civilization and its most vulnerable single point of failure. Recent incidents at power substations across the country have revealed a terrifying reality: a relatively small number of coordinated attacks could plunge vast regions into darkness for weeks or months, with cascading effects that would make Hurricane Katrina look like a minor inconvenience.

The December 2022 attack on two Duke Energy substations in Moore County, North Carolina, illustrated the basic vulnerability. Two individuals with rifles caused a blackout affecting 45,000 people for several days. But this was amateur hour compared to what organized groups could accomplish with proper planning and coordination.

The math is sobering. The Department of Homeland Security has identified roughly 55,000 electrical substations nationwide, but destroying just nine of the most critical ones could theoretically black out the entire continental United States. Unlike the heavily fortified nuclear plants or major power stations, most substations are protected by little more than chain-link fencing and security cameras. Many critical transformer installations sit exposed in rural areas with minimal surveillance and lengthy emergency response times.

What makes this threat particularly insidious is that it doesn’t require sophisticated weapons or technical expertise. The critical transformer equipment that steps down high-voltage transmission lines is custom-manufactured, expensive, and takes 12-18 months to replace under normal circumstances. A coordinated rifle attack, or even the intelligent use of a reciprocating saw, on multiple substations simultaneously could create a replacement bottleneck that extends outages for months across multiple states.

The cascading effects of a decently-coordinated series of attacks would be catastrophic. Within hours, water treatment plants would lose power, leading to pumping capacity failures. Hospitals could switch to backup diesel generators, but their fuel supplies typically last 72 to 96 hours. Cell towers would go dark as their backup batteries drain, as even those with some minimal solar backups would be drained faster than solar can recharge them. Gas stations could not pump fuel; grocery stores and ATM’s stop working – in the case of the grocery stores, that would be because few, if any,m are set up to switch to paper receipts. Supply chains would being to collapse, as refrigerated transport becomes impossible, electronic payment systems began failing, and regional grocery supply centers would not be able to fulfill orders, if they were even able to receive them.

Behind this vulnerability is the very thing that makes modern society as comfortable as we have become accustomed to: Just In Time Delivery. This is the system that dispatches all manner of inventory to retailers, homes and factories at will, usually arriving within 24 to 96 hours after ordering. This means that very few warehouse areas have more than three or four days of stock in their “back rooms”, at best. This is one of the reasons for the videos of stores being emptied in mere hours when a disaster strikes – it’s not simply damage to the structure, but the location’s inability to order replacement stock.

Most Americans have never experienced true grid-down conditions lasting more than a few days. The best estimates indicate that potentially 90% of Americans would be dead within one year of a sustained nationwide blackout due to starvation, disease, and violence. Even regional blackouts lasting weeks would likely trigger mass refugee movements, as happened in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, that local authorities couldn’t manage.

The threat isn’t theoretical. In recent years, domestic extremist groups have conducted surveillance of electrical infrastructure. FBI investigations have uncovered plots targeting substations by nihilistic accelerationists larping as neo-Nazis who believe destroying the grid would trigger societal collapse and racial conflict. The knowledge required for effective attacks are spreading through online forums and training materials.

International actors represent an even greater threat. Chinese and Russian operatives have been caught conducting reconnaissance of American electrical infrastructure. State actors could coordinate cyber attacks on grid control systems with simultaneous physical attacks on key substations, maximizing damage while minimizing the chances of rapid recovery.

And what happens if such a series of attacks do happen? None of the possibilities are good. Aside from the initial casualties of the sick and injured as hospital generators run dry of fuel, and those dying in the panic after the lights go out, the near-term (60 – 90 days) will see vast deaths via starvation, as most people have perhaps only two or three weeks worth of food at home, and human performance degrades fast, the longer we go without food. Rural areas are better positioned, since those areas are food producers by default, but they do not have the capacity to absorb refugees, nor to suddenly step up food production, because of the physics and biology of agriculture: even without the fact that most farmland is sectioned off for corporate, single-crop “monoculture” products, it takes time, at least sixty to ninety days, to grow most plants into nutritious crops that will sustain a human. And although hog hunting in the South does produce meat, it is barely impacting the hog population – and the vast majority of Americans have no comprehension of how dangerous feral hogs really are.

The fix is neither quick, simple nor cheap. Hardening critical substations would cost billions and take years to implement. Installing backup transformer capacity requires massive infrastructure investments that utility companies stridently resist making without punitive federal mandates. Meanwhile, the grid continues operating with vulnerabilities that a competent adversary could exploit with devastating effectiveness.

The uncomfortable truth is that America’s electrical grid was designed for reliability and efficiency, not security. In an era of increasing domestic extremism and great power competition, that design philosophy represents a strategic vulnerability that adversaries understand better than most Americans. The question isn’t whether someone will eventually attempt a coordinated grid attack — it’s whether we’ll address these vulnerabilities before they do.

The only good thing in this, is that if we go down, we will take the reast of the “developed world” with us.

Yay. I guess.

The lights we take for granted could go out faster than most people imagine, and stay out longer than our society could survive. As with many things we report here, you are on your own – after reading this, you cannot claim that you weren’t warned to prepare, because the government will not be able to help you.