The Devil, they say, is in the details…and this is nowhere more true than with nation-states.

The Mists of Time

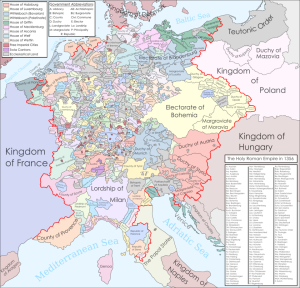

On August 6, 1806, Holy Roman Emperor Francis II performed an unprecedented act: he declared the Holy Roman Empire dissolved. Not abdicated — dissolved. In a single proclamation, he claimed to release all imperial estates from their obligations and declared the thousand-year-old state institution defunct.

But – did he actually have the legal authority to do so?

The Holy Roman Empire had survived invasions, religious wars, and constitutional crises since its founding under Charlemagne. Its complex federal structure, codified most notably in the Golden Bull of 1356, distributed sovereignity among the Emperor and seven Electors who chose him. This wasn’t an absolute monarchy — it was a constitutional arrangement where the Emperor derived legitimacy from election, not divine right alone.

Francis faced genuine crisis in 1806. Napoleon’s war machine had crushed Austrian forces, and had forced most of the tiny German states into his Confederation of the Rhine, while threatening further action against the Empire if Francis maintained his imperial title. Francis, obviously, threw up his hands and simply quit, deciding to try and destory the empire he had inherited at the same time But duress doesn’t create constitutional authority. The question isn’t whether Francis felt compelled to act — it’s whether the act itself was legally valid.

Previous imperial abdications had followed a well established procedure. When Charles V abdicated in 1556, he transferred the crown to his brother Ferdinand, who was then elected by the Electors. The institution continued. Only the office transferred. Francis did something entirely different: he claimed the office itself ceased to exist.

But here’s the constitutional problem: nowhere in the HRE’s imperial law was there a mechanism for the Emperor to unilaterally “dissolve” the Empire. The Golden Bull and subsequent constitutional documents provided for succession, election, even deposition of inadequate emperors. But dissolution? That authority didn’t exist. The Empire was not the Emperor’s personal property to dispose of — it was a corporate entity with distributed sovereignty among hundreds of estates, seven Electors, and the Emperor himself.

Think of it this way: a modern Prime Minister can resign, but cannot abolish Parliament by their resignation. The institution exists independently of any single officeholder. Francis treated the Holy Roman Empire as if his abdication necessarily meant its termination, but the constitutional logic doesn’t support this.

The proper procedure would have been abdication, returning authority to the Electoral College. They could then either elect a successor, declare an interregnum while addressing the crisis, or — if they possessed such authority — negotiate formal dissolution. Francis bypassed this entirely. He acted ultra vires — far beyond his legal powers.

This is not merely an academic oddity. If Francis’s dissolution of the Empire was constitutionally defective, then the Empire was never properly terminated. It would still exist, in abeyance, awaiting constitutional resolution of the issue by competent authorities. The parallel to various royal restoration claims is direct: an improper termination of a state or ruling body does not create legitimacy through passage of time, if the original constitutional breach was fundamentally outside the scope of its parent document.

The Treaty of Westphalia and subsequent settlements treated the Empire’s constitutional arrangements as part of the international order. Francis’ unilateral action disrupted this without proper legal process. Yes, the Empire was functionally dead by 1806 — but “functionally dead” and “legally dissolved” are two very different things.

Okay, But…So What?

Why does this matter now? Europe is facing its own legitimacy crisis. The European Union struggles with democratic deficits, member state frustration, widespread Citizen anger and questions about sovereignty that echo the Empire’s earlier federal complexity. Recent events — Romania’s annulled election, chronic German governmental instability, and questions about republican/democratic institutional stability suggest arrangements once considered permanent might be more fragile than assumed, among many others — indicate that institutional arrangements once considered permanent might be more fragile than originally believed.

Germany’s security services are currently monitoring the various Reichsbürger movements intensely, precisely because these groups attract otherwise frighteningly competent people — elite military officers, civil servants, judges — seeking alternative frameworks to what they see as fundamentally failed institutions. To be clear, most Reichsbürger constitutional theories are deranged nonsense. But — a restoration claim based on Francis II’s procedural defect in dissolving the Empire would be constitutionally defensible in ways “sovereign citizen“-type arguments aren’t.

The Holy Roman Empire was multi-ethnic, federated, and legally complex — arguably a more functional proto-European union than what currently exists. Its constitutional traditions emphasized distributed sovereignty and limited central authority. For Europeans frustrated with Brussels’ centralized in insensitive bureaucracy, that historical model might seem increasingly attractive.

None of this requires believing that restoration is imminent, or even desirable. But it does require acknowledging that Francis II’s 1806 dissolution rested on questionable legal authority, and that constitutional irregularities — even centuries-old ones — don’t automatically become legitimate through time’s passage.

But – What would an attempt at legal restoration look like?

Any claimant would face immediate practical obstacles: no territory, no recognition, and likely harassment from modern German authorities nervous about monarchist movements. Yet the constitutional argument itself remains surprisingly robust. When Juan Carlos returned to Spain in 1975, he didn’t claim the throne by force — he accepted it through a constitutional process during institutional transition. A Holy Roman Empire restoration would require similar conditions: crisis’ severe enough to make a monarchical alternative attractive, yet orderly enough to permit constitutional rather than revolutionary change.

The most constitutionally defensible approach would mirror Francis II’s error in reverse: a claimant declaring themselves ‘Interim Emperor‘ pending the reconvening of the Electoral College. This acknowledges the procedural defect — no proper dissolution occurred — while avoiding claims to absolute authority. It’s restoration through constitutional humility, not monarchical assertion.

The Emperor dissolved his Empire. The question is whether he had the right to do so. And if he didn’t, what does that mean for the constitutional status of a thousand-year institution that may never have been properly put to rest?