When people think of military actions, those thoughts are usually centered on frenetic Hollywood action sequences. There are the occasional meetings/briefings where the stock, lantern-jawed heroes get their orders from a grizzled, crusty-looking officer, who occasionally pushes their “knife hand” across what is probably a real enough map of…somewhere, but probably not the “somewhere” of the show.

The effect is even more divorced from reality when watching the average news broadcast: the tall, swarthy, lantern-jawed heroes are almost always either completely hidden by helmets and body armor, or are somewhat short, usually bald, and squinting through their sunburns and badly wind-dried skin. The vehicles and surrounding terrain are anonymous and dusty (or heavy with tropical foliage, or a blasted city-scape) – things are certainly happening, but the viewer has little context. The reporter delivering the story probably has even less.

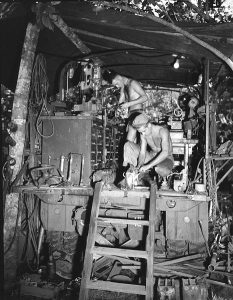

The grizzled and lantern-jawed stock characters from Central Casting do occasionally appear – and are even frequently as heroic as Hollywood portrays them to be – but the above images (real and fictional) obscure the reality: the Grunts who have to carry out the mission have their tasks explained to them by sleep-deprived, over-caffeinated, and hyper-stressed troops suffering from ulcers, who have likely been awake for over 24 hours, straight, and have been monitoring units in combat with the enemy, while coordinating artillery fires, air support, medical evacuations, resupply, reinforcement and probably armored support, as well…and have to get creative on short notice when one, some or most of those things are not available, because of shipping delays, bad weather, enemy attacks on the supply lines and just plain bad-to-non-existent maintenance means that something else needs to be found to help the Grunts get the job done.

Those officers and troops, punchy from lack of sleep, are the Staff.

In the “old days”, military staff work was not overly taxing, by today’s standard. Literate officers and troops (read the letters of some officers on campaign in the old days – yikes) made the decisions and wrote the orders, trying to be as clear – yet couched and polite – as the writing conventions of the time allowed. Unit sizes were rarely above the Brigade level (c.3-5,000 troops), and the “optempo” (“operations tempo”, or, the pace of operations) was measured by how far a unit could march in a day. By modern standards, it was quite sedate. The only real “specialization” in the military staff were the Surgeon (for obvious reasons) and the Quartermaster, who handled the acquisition of supplies; this last position, while recognized as highly important, was not much sought after, as it was viewed as a rather menial task.

That all began to change with three wars in the 19th Century: The American Civil War of 1861-1865, the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. The actual mechanism for the increase to optempo in those wars was the railroad.

The railroad revolutionized warfare in a way not seen before in land warfare. In the past, like cargo, the fastest and most efficient way to move troops more than 100 miles was by water. By 1863, the United States Military Railroad (USMRR) was able to transfer some 25,000 troops a distance of 1,200 miles in just 12 days. The USMRR did this by creating a dispersed staff of railroad schedule planners who communicated via telegraph to coordinate their movement plans. In 1866, the Prussian Army – having sent observers to both sides of the American Civil War – calculated that they could concentrate 285,000 troops in twenty-five days, and used this ability to overwhelm Austrian forces. Four years later, Prussia would demonstrate the defensive advantage of the railroad, by using their internal rail system to rapidly shift their outnumbered troops around the country to first blunt, and then counterattack the French invasion, resulting in not simply the defeat of France, but the capture of an Emperor and the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine, specifically because they had established a “railway section” as a part of their ‘general staff’ system after the return of their observers from the American Civil War.

This is not, however, an article on the military use of railroads. Instead, it shows the first real expansion of the military staff system since the days of Napoleon, and going well beyond his reforms.

Napoleon Bonaparte created what we now refer to as the “Continental Staff System”, minutely categorizing and specializing roles that had previously been handled somewhat haphazardly. As armies began to grow in size and complexity after Napoleon, the old staff methods simply could not keep up. Even in the case of Napoleon’s own staff reforms, they could barely keep up with the demands of La Grande Armée. The US Army, first, then quickly followed by Germany, began to make significant reforms and expansions.

However, this was not a streamlined or consistent process. In fact, in Germany’s case, it became a decided negative, as the German General Staff took the statistical process too far, imparting a rigidity that more or less completely ignored the Clausewitzian warnings about “friction” and the “fog of war”. This rigidity contributed to the failure of the Schlieffen Plan and led directly to the hell of trench warfare on the Western Front of World War 1.

In the modern day, the staff system has evolved to the point where it can swiftly alter itself to account for new technologies. As radio replaced visual-sight signaling, dispatch riders, carrier pigeons and the telegraph, staffs were increasingly able to effectively control and support their subordinated commands in real-time. Today, that progression includes satellite communications and (theoretically) secure internet connections, as well as incorporating intelligence from ground- and air-based drones.

In order to better streamline the core functions of a staff, tasks and responsibilities are divided between departments led by specialized officers. Even in the last 30-odd years, there has been expansion and readjustment, as some of the current offices either did not exist in the 1980’s, or were considered to be part of a “Special Staff” section, created on an ‘as needed’ basis.

Currently, there are a total of nine departments recognized as part of the Continental Staff System. These nine offices scale upwards, as designated by a prefix letter code (see below), and generally only begin to appear as part of a battalion-level staff. The nine offices in general use are:

-

- Manpower or Personnel. This office manages the more mundane, non-combat personnel-management tasks of a unit, such as record-keeping and handling pay for the troops.

- Intelligence and Security. This is the office with the unenviable task of trying to predict what the enemy in a local area are planning. However, their ‘side functions’ are much more extensive, and include everything from weather monitoring and map making, to cultural and demographic surveys to refine information that was likely glossed over by their national-level counterparts.

- Operations. This is the office that actually controls the troops in the field. The unit commander, their executive officer (i.e., the “second in command”) and the “-3” officer (who is effectively 3rd in command) direct operations, through the mechanism of the “command post” system.

- Logistics. Logistics – what used to be called the “Quartermaster” office – is one of those dreary, ho-hum functions that people only get annoyed over when they either fail, or when someone points out that the military unit in question is incapable of functioning if they ignore the “4-Shop”. If your logistical plan is deficient in the civilian world, that is annoying and inconvenient. In the military world, bad logistics lose battles, campaigns and wars.

- Plans. This is where you will find those grizzled old officers making knife-hands over a map. The Plans office has to take the commander’s ideas and vision, lay them out coherently on a map, then write the orders to the various sub-units to carry out those plans.

- Signals (i.e., communications or IT). “Signals” are the people who run the radios, and make sure the computers are working right. They will also occasionally restore telephone service to a town or city…usually inside of 36 hours.

- Military education and training. Exactly what it says – there are always new things coming out, that troops need to be trained on, which can also include seemingly non-military course like the dreaded “Personal Finance” course. In case anyone is wondering why distance-learning courses like that are offered, troops who badly manage their pay are frequently preoccupied, hyper-tense and distracted in the field; this leads to very unpleasant results for them, and likely everyone in their general vicinity.

- Finance and Contracts. Also known as resource management. This is the department that handles buying tools, materials and food from the local area. In the “home country”, these kinds of contracts are normally handled at higher levels; when operating in a foreign country, however, the situation frequently dictates that a units needs to let contracts with the locals…which not only gets the unit supplies locally, easing the logistics burden of the higher commands, but also helps a local economy that may have been destroyed and needs more than simple hand-outs of cash.

- Civil-Military Co-operation (CIMIC) or “civil affairs”, as well as PIO functions, who generally deal with the news media.

As noted above, there are a variety of letter designators for these staff functions, depending on the size and/or function of the unit in question. The most commonly used designators are:

-

- A, for air force headquarters.

- C, for combined headquarters (multiple nations) headquarters.

- F, for certain forward or deployable headquarters.

- G, for army or marine general staff sections within headquarters of organizations commanded by a general officer and having a chief of staff to coordinate the actions of the general staff, such as divisions or equivalent organizations (e.g., USMC Marine Aircraft Wing and Marine Logistics Group) and separate (i.e., non-divisional) brigade level (USMC MEB) and above.

- J, for joint (multiple services) headquarters, including the Joint Chiefs of Staff).

- N, for navy headquarters.

- S, for army or marines executive staff sections within headquarters of organizations commanded by a field grade officer (i.e., major through colonel) and having an executive officer to coordinate the actions of the executive staff (e.g., divisional brigades, regiments, groups, battalions, and squadrons; not used by all countries); S is also used in the Naval Mobile Construction Battalions (SeaBees) and in the Air Force Security Forces Squadron.

- U, is used for United Nations military operations mission headquarters.

- CG, is unique to the US Coast Guard.

While there is certainly much more to military staff functions than this brief outline, the goal was to introduce the Reader to the idea behind the Military Staff, in a general way. If you would like more information on the subject from the source, check out the US military’s field manual on the subject, FM 6-0 – Commander and Staff Organization and Operations, in print here, or as a pdf download directly from the US Army, here. (Note that most military manuals in the United States are unclassified and publicly available for anyone to own – if it’s classified, you will definitely know, and you are definitely on your own, in that regard.)