What’s old is new, apparently. Everyone wants more land…even if the have to build it themselves.

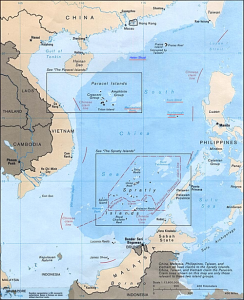

While American attention remains fixated on Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, as well as on Venezuela, a different story is unfolding beneath the surface in the Far East. Vietnam has been building artificial islands at a pace that should make Beijing envious, and the most remarkable aspect isn’t the construction — it’s China’s silence.

Since October of 2021, Vietnamese dredgers have created over 930 hectares of new land across the Spratly Islands, transforming 21 previously marginal outposts into fortified positions complete with ports, helipads, munitions depots, and the infrastructure for military runways. That’s roughly 70 percent of what Communist China built during its infamous “Great Wall of Sand” island-building campaign from 2013 to 2017. At the current pace, Vietnam will match China’s total reclaimed area within two years.

The scale is impressive, but the strategic implications are much more so. Take Bark Canada Reef — once barely above water, it now hosts 2.8 kilometers of reclaimed land with foundations laid for a 2,400-meter runway capable of handling military transport aircraft and bombers. Pearson Reef has expanded to nearly 1.3 square kilometers. Tennent Reef, Ladd Reef, South Reef — the pattern repeats across the archipelago: dredge through lagoons, pile sediment into sandbars, build infrastructure.

The construction follows a clear, “cookie-cutter” military logic: Each reef features identical clusters of buildings arranged around central courtyards, munitions depots surrounded by blast walls, and ports capable of servicing Vietnam’s Gepard-class frigates. These aren’t research stations or fishing outposts. They are naval forward operating bases, designed to extend Hanoi’s ability to sustain naval deployments far from the mainland. Ships can now resupply, refuel, and rotate crews without returning to the coast, dramatically extending patrol durations in contested waters.

What makes this particularly interesting is China’s muted response. Beijing, which has spent years aggressively confronting the Philippines over far smaller provocations, has issued only perfunctory diplomatic statements about Vietnam’s construction. No coast guard harassment. No water cannon attacks. No military posturing. The contrast is stark: the Philippines controls just nine land formations in the Spratlys and faces constant Chinese pressure, while Vietnam fortifies 29 positions and Beijing mostly looks the other way.

Three factors explain this disparity. First: bandwidth — China is fixated on the Philippines, which has strengthened its defense ties with the United States, opened additional bases to American forces, and conducted recent joint exercises with Washington’s Pacific allies. Beijing opening a second front against Vietnam risks unifying ASEAN against Beijing, something Chinese strategists would rather avoid.

Second: historical precedent — Vietnam has been expanding in the Spratlys since the 1970s, even seizing a few formations from China itself during a bloody 1988 skirmish that killed 64 Vietnamese sailors. From Beijing’s perspective, Vietnam’s current expansion, while larger in scale, isn’t fundamentally new behavior. The Philippines’ recent pushback, by contrast, represents a more pressing challenge to Chinese dominance.

Third: strategic ambiguity — Vietnam maintains partner status in BRICS, attended Beijing’s Victory Day ceremony, and recently finalized an $8 billion arms deal with Russia. When the Trump administration imposed reciprocal tariffs on Vietnam, President Xi visited Hanoi and signed dozens of economic agreements. China remains Vietnam’s largest trading partner with $25 billion in bilateral trade and over $31 billion in cumulative foreign direct investment. Beijing calculates that Hanoi can be managed through economic incentives rather than confrontation.

But, there is obviously a lot of recent history behind this.

The 1988 incident was hardly the first time Vietnam and China had come to blows, however. In February 1979, China launched a punitive invasion of northern Vietnam with 200,000 troops, ostensibly to “teach Vietnam a lesson” for its invasion of Cambodia and alignment with the Soviet Union. The month-long war proved costly for both sides — China claimed 6,900 killed while Vietnam reported 10,000 casualties, though actual figures were likely higher on both sides. Chinese forces captured several provincial capitals before withdrawing, but the operation exposed serious deficiencies in the People’s Liberation Army, which hadn’t fought a major conflict since the Korean War. Importantly, it is vital to remember that in the 1979 conflict, Vietnam fought on two fronts, with c.150,000 troops in Cambodia, while holding off a c.200,000 man Comminust Chinese army — no mean feat, on its own.

More importantly, it established a pattern: Vietnam demonstrated it wouldn’t be intimidated by Chinese military pressure, while Beijing learned that forcibly changing Vietnamese behavior carried steep costs. This historical context helps explain today’s dynamic — China remembers that Vietnam, unlike the Philippines, has proven willing and able to inflict significant casualties in defense of what it considers its territory.

The difference in Beijing’s reaction is telling. While the Philippines has proven that it can certainly fight invaders defensively, it has never actually fought a large-scale war on its own. The largest battle Filipino forces have fought on their own was the five month long siege of Marawi in 2017 – an urban warfare, COIN operation against Islamic State-affiliated guerillas.

Vietnam’s island-building is only part of a broader military transformation. In April 2025, Hanoi finalized a $700 million deal with India to acquire BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles — both ground-based launchers and air-launched versions for its Su-30 fighter jets. The BrahMos represents a significant capability upgrade: it flies at Mach 2.8, carries a 300-kilogram warhead, and can strike targets up to 290 kilometers away, with precision guidance that makes it extremely difficult to intercept. The missile’s sea-skimming trajectory — flying just 3-4 meters above the water’s surface—and terminal maneuvering make it particularly lethal against naval targets. Former BrahMos Aerospace CEO A. Sivathanu Pillai noted that the missile’s high speed combined with its heavy weight makes it about 15 times more lethal than conventional anti-ship missiles: “Any other anti-ship missile will only leave a hole in the hull of the attacked ship, but the Brahmos missile will completely obliterate the target.” Combined with Vietnam’s reported acquisition of 40 Su-35 fighter jets from Russia, including advanced electronic warfare systems, these weapons transform Vietnam’s fortified islands into what military planners call “unsinkable aircraft carriers.”

The strategy is clear: create facts on the water faster than China can react, hoping to shape a reality too costly for Beijing to reverse. Whether Beijing’s restraint holds, or whether Vietnam’s bet on “hard power” over diplomacy eventually triggers the confrontation both sides claim to want to avoid, remains to be seen.

So — Why should you care? You should care, because approximately $5.3 Trillion dollars worth of global trade — about 24% — flows through this area. If you are one of the few people who can legitimately say that you have nothing in your home that cam from overseas…this still impacts you, because the systems you rely on come off of trans-ocianic ships. And, a major disruption of trade in this area will up-end the carefully curated global system of trade that all nations — including the United States — now depend on. And if you don’t believe that, just refresh yourself about the global impact of the grounding of the container ship EVER GIVEN in 2021…and that was one ship.

For now, the South China Sea is being remade one dredger-load at a time…and not by the country everyone’s watching.