Background

Iran is an almost unimaginably ancient culture. Only Egypt comes even close in age.

Iran – also known as “Persia“, from the Greeks – played pivotal roles in both Greek and Jewish history. Iran was, for good or ill, the external unifier of the fractious Greek city-staes. It was also the saviour of the Jews, when Cyrus the Great not only freed the Jews from their Babylonian Captivity, but helped them to build the Second Temple (Isaiah 44:28, Isaiah 45:1, Ezra 1, and 2 Chronicles 36). Sasanid Persia was the state that went to war with the Eastern Roman Empire after the assassination of the Roman Emperor Maurice, inadvertantly making room for the rise of Muhammad and Islam.

But, Iran was never happy under Islam, not simply because the form of Islam in Iran – Shia – was at odds with mainstream Sunni Islam, but because it was adamantly opposed to being dominated by the Ottoman Empire. This back-and-forth situation continued into the 20th Century, until Reza Pahlavi overthrew the ruling Qajar dynasty, and was made Shah (“King“, approximately) in 1921.

Reza Pahlavi, as Reza I, was removed from power in 1941 by an invasion by Britain and the Soviet Union, because they wanted to use Iran as a supply route to the Soviet state, and were afraid that Reza I would remain neutral, if not actually ally with Nazi Germany. The two Allied powers sent Reza I into exile, and placed his young son, Muhammad Reza II, onto the throne.

This situation continued for the next thirty years, as the new Shah worked carefully to first secure his throne, then begin the slow and painful process of bringing Iran into the modern age…a process which was well on its way to success by 1978, building up Iran’s oil, manufacturing and electronics sectors, and becoming the most solid ally of the United States in the region, far more so than Israel…when it all went off the rails.

Power Play

When the Iranian Revolution erupted in 1978, Washington’s response puzzled many observers. The Carter Administration seemed strangely passive as Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s grip on power began to crumble. While historians typically attribute this to Carter’s “naive and kindly nature”, human rights concerns over the Shah’s perceived increasingly brutal crackdowns on internal dissent and diplomatic fumbling, a closer look at the Shah’s military ambitions reveals a much more complex story — one where America’s most reliable Middle Eastern ally had become something Washington never quite intended: a genuine regional superpower with its own agenda…and an existential threat to the Soviet Union.

By the late 1970s, the Shah had transformed Iran into a regional military colossus. The ruler openly declared he wanted the Iranian armed forces to become “probably the best non-atomic” military in the world, and he was well on his way to achieving that goal. Iran became the only foreign customer ever for the F-14 Tomcat, America’s most sophisticated fighter jet at the time, ordering 80 of the aircraft along with 714 AIM-54 Phoenix missiles in what was then the largest single foreign military sale in U.S. history.

But the F-14’s were just the beginning. The Shah sought to transform the Imperial Iranian Navy into not only the predominant force in the Persian Gulf but a naval force capable of patrolling the Indian Ocean. His vision extended far beyond defending Iran’s borders. He wanted power projection capabilities that would establish Iranian dominance from the Mediterranean to South Asia.

This was not mere vanity. The Shah had positioned himself as the guardian of Western interests in the region, and initially, Washington welcomed this role. Following Britain’s 1971 withdrawal from the Persian Gulf, the Nixon administration embraced Iran as the primary pillar of regional security, offering the Shah what amounted to a blank check for military purchases. Any non-nuclear weapons system Iran wanted, America would sell them.

Underlying this buildup, however, was a very simple psychological perspective: the Shah was bitter over his father’s fate, and how he came to power as a puppet-king. His relentless rearmament program was his hedge against that happening again.

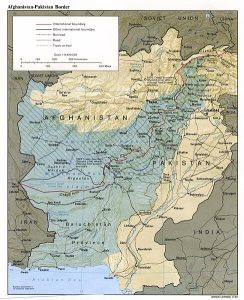

Yet the very success of this policy created an uncomfortable paradox. Iran’s conventional buildup was turning it into the primary military power between Israel and India, and the Shah’s ambitions increasingly diverged from American strategic interests. Pakistan was a developing country while Iran had the world’s fifth-largest military, a strong industrial base, and was the clear regional superpower.

The Shah’s regional behavior began to quietly raise eyebrows in some sectors of Washington, D.C. He openly supported Pakistan in both the 1965 and 1971 wars against India, providing free fuel and military equipment. In June 1974, when asked if Iran would develop nuclear weapons like India had just tested, the Shah declared: “Without any doubt, and sooner than one would think” — before walking back the comment to placate international concerns.

Perhaps most significantly, Iran’s geographic position adjacent to Soviet Azerbaijan, combined with its growing strike capabilities, meant the Shah commanded theoretical leverage over Soviet oil infrastructure at Baku. This was a double-edged sword: useful for deterring Soviet aggression, but also giving Iran independent strategic options that could complicate U.S.-Soviet relations during an era of détente.

But for the Soviets, their battle-planners saw the threat immediately: a capable Imperial Iranian Air Force could threaten the Soviet’s oil jugular: the port city of Baku, on the Caspian Sea – which in the 1970’s supplied some 30% of the Soviet Union’s oil reserve. A successful Iranian strike on Baku, especially if it came during a war in Europe with NATO, would result in complete defeat and capitulation to the West. As long as the Shah had a “toy army”, he was no threat to the Communist state.

The question was: Just how capable was the Shah’s military in the mid-1970’s?

In 1973, the Soviet’s got their answer.

The Dhofar Intervention: Iran’s Dress Rehearsal

Perhaps the clearest demonstration of Iran’s emerging regional power — and the strategic dilemma it posed — came not in the Persian Gulf itself, but on the Arabian Peninsula. Between 1973 and 1976, the Shah deployed over 4,000 Iranian troops to Oman to help Sultan Qaboos crush a Marxist insurgency in the Dhofar region. The operation, conceived entirely by the Shah himself, included an Iranian infantry brigade, sixteen jet fighters, naval support, and critical helicopter transport capabilities that proved decisive in the counterinsurgency campaign.

It was not simply the hardware, however. It was that Imperial Iranian forces showed in Dhofar that they actually knew how to employ the weapons and tools they Shah had supplied them with. In the military sphere, that scope of training and capability is far more important that the mere tools themselves.

The Shah justified this intervention by claiming he needed to defend the Strait of Hormuz from the threat of communist control. But the operation demonstrated something more profound: Iran now possessed the capability and will to project military power across the region independently. Iranian forces operated far from their borders, coordinated multi-domain operations, and effectively determined the outcome of a neighboring country’s civil conflict — all without requiring American permission or direct U.S. involvement.

For Washington, Dhofar was simultaneously reassuring and alarming. The Shah had proven himself a capable regional policeman willing to contain Soviet-backed insurgencies. Yet, he had also demonstrated that Iran’s military reach now extended well beyond merely defensive operations. The same expeditionary capabilities deployed against Marxist rebels in Oman could theoretically be used to pursue Iranian interests elsewhere — including objectives that might not align with American strategic goals.

For the Soviet Union the fact that Dhofar was “limited”, in a technical sense, was irrelevant. The Imperial Armed Forces had proven that they were good enough, that Soviet battle calculus had to recognize that the Shah had built the equivalent of a NATO field army on its southern frontier, an army that was capable of striking a fatal blow at the Soviet Union in a full-scale war.

Endgame

By 1978, American officials increasingly realized that they were facing a critical dilemma they had helped create. The Shah’s military modernization had proceeded so rapidly that Iranian aircrew simply couldn’t be trained fast enough to operate all the aircraft, with hardware literally piling up on docks. A Senate committee estimated Iran could not go to war without U.S. support on a day-to-day basis, yet the Shah was increasingly asserting his independence…yet the Iranian’s were not deficient in their training and readiness, and had proven themselves to be a capable and dangerous armed force with a regional reach.

Thus, when a Soviet-aided “revolution” threatened the Pahlavi regime, Carter’s response was notably restrained. The administration pressured the Shah to implement political reforms rather than crack down decisively on protesters. By November 1978, U.S. Ambassador William Sullivan alerted Washington that the Shah was “doomed”, yet the administration actively discouraged the Iranian military from launching a coup to save the monarchy.

The conventional narrative on the US failure to support the Shah usually blames this on Carter’s human rights idealism and/or poor and naive intelligence. But there’s another possibility worth considering: that after a decade of arming the Shah to the teeth, many in Washington now saw that an independent, militarily powerful Iran — one capable of threatening fundamental Soviet interests without American permission or dominating regional neighbors — might not serve U.S. interests as reliably as previously assumed.

The Shah had done exactly what Nixon and Kissinger had asked: he’d built a militarily capable regional superpower. The question Carter faced was whether that superpower would remain aligned with American objectives — or become a force unto itself. When the moment came to save the Shah’s regime, Washington hesitated. Whether that hesitation stemmed from human rights concerns, fear of failure, or quiet recognition that the United States had created a monster it would not be able to fully control, remains one of the revolution’s enduring questions.

Whatever the case, the Carter administration’s actions regarding the Shah’s declining health in his exile indicate that far darker maneuvers may have been in play.

In the end, the failure of Western support to the Shah resulted in five decades of horror, around the world. Whether that is about to come to an end or not, remains to be seen.