The war in Ukraine, once again, has revived the tired old saw about the armored combat tank being “obsolete” in warfare, because – drones…and, like every other time someone said something this silly, it has been proven categorically false. Not least, in the fact that older tanks – not simply older designs, but physical vehicles that are older than their crews…and sometimes, older than the entire crew, combined.

Both Russian and Ukrainian tank crews are driving the full panoply of ex-Soviet designs long considered not simply obsolescent, but absolutely obsolete. From T-54/55‘s, T-62‘s, T-72‘s and T-80‘s, these old warhorses still grind around the modern battlefields of Ukraine in large numbers, a function of the truly massive numbers of the vehicles produced during the Cold War.

But these vehicles also still fight in battles all over the world, as most of them were exported in large numbers to anyone aligning with Soviet ideology – honest or not – or, later, any state with very modest cash reserves.

In this, the 1990-1991 Gulf War – “Operation Desert Storm” – created some fundamental misunderstandings about old armor, “brain bugs” that have metastasized over the decades, creating truly insane levels of incompetence (but we’ll talk about “Force Design 2030” in a later article). Among those were the general idea that Soviet vehicles were grossly inferior to western designs, when the reality was abysmally poor training, logistics and leadership on the Iraqi side.

The M60A3 main battle tank was considered “old” during Desert Storm; only the US Marine Corps fielded them in that conflict, when the Marine Corps still had tank units (“Force Design 2030” Delenda Est). Even with hasty add-on “reactive armor“, the -60’s were viewed as being dangerously under-armored, going hand-in-hand with its 105mm main gun, which had been replaced in its successor, the 120mm cannon of the M1 Abrams.

And yet – the United States still maintains M60A3’s in “deep storage”, in places like the Sierra and Anniston Army Depots, despite parking older-model M1’s in the same storage lots.

But – why?

When the United States retired its last M60 Patton tanks from front-line service in the 1990’s, conventional wisdom suggested this Cold War workhorse would fade into history alongside other relics of the Soviet-American standoff. Instead, something curious happened: nations around the world began investing serious money into modernizing their M60 fleets rather than replacing them with newer designs. From the deserts of the Middle East to the mountains of Taiwan, the M60 has been experiencing a quiet renaissance that tells us something important about practical defense economics.

The M60 entered American service in 1960 as a counter to Soviet tank development, eventually seeing production of over 15,000 units, in various models. It fought in multiple Middle Eastern conflicts, performed credibly in Desert Storm, and became one of the most widely exported tanks in history. By most measures, it should be obsolete — after all, its basic design is now 65 years old. The M1 Abrams replaced it in U.S. service decades ago, and even the Abrams is facing questions about its age in modern warfare.

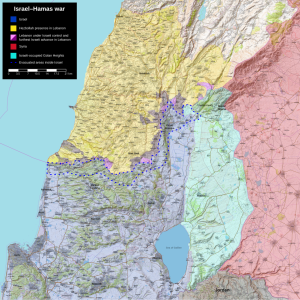

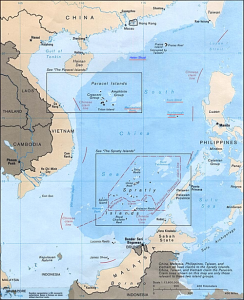

Yet in 2023, Taiwan awarded a contract worth hundreds of millions to upgrade 460 M60A3 tanks with new fire control systems, improved armor packages, and 120mm main guns. Turkey has upgraded hundreds of M60s with indigenous modifications, creating the M60T “Sabra” variant, which have seen extensive combat in Syria. Egypt operates over 1,700 M60’s with ongoing modernization programs. Israel, which originally developed many of the upgrade packages now used worldwide, continues operating upgraded M60s alongside newer Merkava tanks. Even smaller nations like Bahrain, Jordan, and Morocco maintain modernized M60 fleets.

The economics tell the story. A new main battle tank costs anywhere from $6-9 million per unit — and that’s for Russian or Chinese models. Western tanks like the M1A2 Abrams, Leopard 2A7, or British Challenger 3 run $8-15 million each. Comprehensive M60 modernization packages, by contrast, typically cost $2-4 million per tank. For a nation maintaining a battalion of 58 tanks, that’s the difference between a $120 million upgrade program and a $400-600 million replacement program, not including the necessary retraining and new logistics chains. When you’re not facing adversaries equipped with the latest Russian or Chinese armor, that cost differential becomes compelling.

But the financial argument only explains part of the M60’s longevity. The platform offers practical advantages that newer designs sometimes sacrifice. At roughly 52 tons combat weight, the M60 can cross bridges and operate on terrain that won’t support the 70-ton M1 Abrams. Its fuel consumption, while substantial, doesn’t approach the gas-turbine Abrams’ notorious thirst. The mechanical simplicity of its diesel engine means maintenance doesn’t require the specialized expertise that more sophisticated platforms demand — a critical factor for smaller militaries with limited technical infrastructure.

Modern upgrade packages address the M60’s original shortcomings remarkably effectively. New fire control systems with thermal imaging, laser rangefinders, and digital ballistic computers bring targeting capabilities close to contemporary standards – in an environment where “close” still counts. Explosive reactive armor tiles, cage armor, and composite armor packages significantly improve survivability against modern anti-tank weapons. Some variants mount 120mm smoothbore guns — the same main armament found on current M1A2 Abrams tanks. Engine upgrades improve power-to-weight ratios. The result is a platform that, while not matching the latest MBT’s in every parameter, provides legitimate armored combat capability at a fraction of the cost.

The strategic calculus matters too. Many nations employing M60s face threats from irregular forces, not peer militaries with modern tank armies. In counterinsurgency, urban warfare, or defensive operations, an upgraded M60 provides mobile protected firepower that is perfectly adequate to the mission. Turkey’s experience in Syria against Kurdish forces demonstrated that properly supported and employed, modernized M60s remain effective in contemporary combat environments — though they also verified the main battle tank’s well-known vulnerabilities when employed without adequate infantry support or air cover.

There’s a broader lesson here about defense procurement. The endless pursuit of cutting-edge capability often produces systems too expensive to acquire in meaningful numbers, too complex to maintain, and too precious to risk in actual combat. The M60’s ongoing renaissance suggests an alternative approach: proven platforms, continuously modernized, maintained in sufficient numbers to matter operationally. It’s not glamorous, and it doesn’t win promotions for procurement officers, but it might represent more actual combat power per defense dollar than many more modern and “sexier”, alternatives.

As so-called “hybrid warfare“, drone technology, and precision fires force reconsiderations of armored combat tactics, questions about the main battle tank’s future persist. But for nations prioritizing practical capability over theoretical performance, the upgraded M60 offers a pragmatic answer: sometimes the best tank for your situation isn’t the newest one — it’s the one you can afford to field in useful numbers, while still paying your soldiers, that will continue to get the job done.