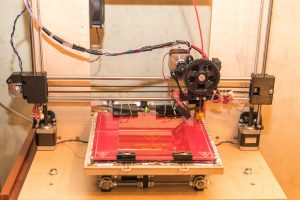

Additive Manufacturing – better known as “3D Printing” – has been increasing in popularity and capability, while decreasing in price, for the last thirty years. Today, many very capable printers can be had for well under US$500. The products produced range from simple objects to complex and detailed models, both of mechanical parts, as well as people. As well, 3D printing has begun to expand into using metals, which can be heated after printing to make the printed items strong enough for working applications.

Naturally, as soon as the technology’s capabilities reached a certain, ill-defined threshold, minds in many quarters began studying the possibility of military applications. While many do see “potential”, is that potential actually useful “downrange”?

Military forces have – obviously – changed significantly over the millennia. A soldier of Sargon the Great didn’t really require a great deal in the way of supplies, weapons or equipment. Indeed, in many cases, a soldier of Sargon may likely have been able to make much of their needed weapons and equipment on the spot, if they had the time and resources. All that really needed to be supplied to the soldier was food and water (for both troops and animals), and perhaps some large parts for siege engines.

As time and technology progressed, of course, weapons and equipment became increasingly specialized and difficult to manufacture. But, while troops could still forage for food and water, once the weapons were delivered, they were comparatively uncomplicated to both use and work on, should repairs be required in the field.

By the end of the 20th Century, of course, weapons, ammunition and much of the soldier’s equipment had advanced to the point where the vast majority of troops in all armies had only a nominal idea of how their weapons worked, let alone how to make or repair them.

These were all factors taken into account by those studying additive manufacturing for military purposes.

As is it possible, and relatively easy, to pack a “job shop” or three into shipping containers, along with some raw material stock and possibly parts blanks (although 2- and 3-D pictures, animations and mechanical drawings are far easier with digital reference libraries that can “live” on computers, or even on microfilm archives), making repair parts for many weapons and vehicles are not overly taxing for most units in the field. Plus, there are no questions concerning how strong or durable the field-manufactured parts are…after all, armies are some of the most conservative organizations in history. As a result, there are few specifically military applications, at present, where additive manufacturing can excel over conventional methods…

…But then, came Defense Distributed.

Inevitably, someone was going to make a firearm using additive manufacture. While the saga of Defense Distributed is too complicated to wade through here, the point is that – like Britain’s P.A. Luty before them – Defense Distributed proved that making firearms at home was not that complicated a process, if a person could obtain some very basic materials and tools.

Now, both the “3-D Printed Gun” from Defense Distributed, as well as Luty’s 9mm submachine gun, were – being charitable – both crude, barely-usable weapons. While Luty’s design is occasionally manufactured by criminal gangs in parts of the world with very strict firearms laws, the fact of these weapons’ existence simply proves the points made by both Defense Distributed and P.A. Luty, that no matter how strictly a state tries to enforce restrictive gun control, people who want firearms will get them somehow, even if they have to make them. But, in the law enforcement and military spheres, 3-D firearms remained crude and barely usable, even if they were dangerous.

This all began to change in 2019, when the FCG-9 appeared, designed by a shadowy German-Kurdish anti-gun control activist known as “JStark1809” (who, incidentally, was tracked down in 2021, using financial transaction records; two days after a raid that found no weapons in his residence, the 28-year-old JStark1809 was found dead in his car of, according to the coroner, a “heart attack”).

The FCG-9 is an altogether different 3-D animal, as it appeared in the hands of a dissident IRA splinter group in a parade during Easter of 2022 and – much more significantly – it is reportedly in use by anti-junta rebel groups in Myanmar, beginning in 2021. Being made of 3-D printed media, with a few steel parts for strength, the 9mm weapon is easy to mass-produce in guerrilla workshops, and is apparently far more reliable and useable than either Defense Distributed’s or Luty’s deisgns, further reinforcing the ridiculous nature of restrictive firearms laws.

But…How useful is this technology to an army? Well, beyond the obvious utility for guerrilla forces, as mentioned above, the answer is ‘not much’. As also pointed out above, there are far cheaper and more conventional ways to manufacture spare parts for military-grade vehicles and weapons

3 thoughts on “Additive Manufacturing: Ready For War, Or Blind Alley?”