For the longest time, at least fifty years, military forces in the West – and especially in the United States – have held fast to the dream of “clean” warfare, where civilian casualties are greatly minimized, if not eliminated. This dream grew out of the nightmare of World War 2’s “Strategic Bombing” campaigns, which were not simply failures, overall, but verge into war crimes territory, if one looks too closely.

While technically requiring fewer weapons dropped, as “smart bombs” are certainly more accurate, the dream of airpower alone ending wars is still a phantasm of science fiction – for all the damage precision munitions can inflict, airpower alone stopped neither Saddam Hussein, nor the Taliban, nor the “Islamic State”. Those forces were definitely damaged by technology, but that damage did not stop those forces on their own, by any stretch of the imagination, or suspension of disbelief.

Modern militaries have spent decades cultivating an image of warfare transformed by technology — conflicts resolved through clean, precise strikes that eliminate threats while sparing innocent lives. Defense contractors promote weapons that promise “one target, one bomb” accuracy. Military briefings showcase grainy video footage of munitions threading through windows and down ventilation shafts. Politicians assure anxious publics that twenty-first century warfare has evolved beyond the brutal arithmetic of earlier conflicts.

The reality on the ground tells a different story.

The Promise of Precision

The evolution of precision-guided munitions represents genuine technological achievement. During the 1991 Gulf War, only 9% of munitions were guided, yet they accounted for 75% of successful hits, proving 35 times more effective per weapon than unguided ordnance. Modern systems like the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) can achieve circular error probabilities of approximately 20 feet, transforming standard “dumb bombs” into satellite-guided weapons for roughly $20,000 per kit.

These capabilities have fundamentally changed how militaries plan operations. Where previous generations of commanders compensated for inaccuracy through overwhelming volume — dozens, if not hundreds, of aircraft dropping hundreds or thousands of bombs to ensure target destruction — contemporary planners can theoretically strike with surgical economy. The technology exists, and in controlled conditions, it performs as advertised.

But technology is only one variable in an equation that includes intelligence, decision-making, environmental conditions, and the fog of war. These factors, environmental and otherwise, have not changed for millennia, and are unlikely to change anytime soon.

“Accuracy” Is Not “Effectiveness”

The critical distinction between “accuracy” and “effectiveness” undermines much of precision warfare theory. A weapon might strike precisely where it was aimed while failing utterly to achieve its intended effect, a phenomenon researchers call the “Precision Paradox“.

Consider the 2003 strike against “Chemical Ali” — Ali Hassan al-Majid, Saddam Hussein’s cousin and a high-value target. Two JDAM satellite-guided bombs hit his residence exactly as planned. The strike was accurate. It was also completely ineffective — Chemical Ali survived and remained active for months. When targets are hardened, mobile, or simply more resilient than anticipated, accurate strikes create a destructive feedback loop: the initial precise attack fails, requiring follow-up strikes, then more strikes, with each iteration expanding the circle of destruction and increasing civilian casualties.

This pattern repeated throughout recent conflicts. In battles like the siege of Mosul, accurate but ineffective strikes accumulated, generating precisely the widespread destruction and civilian harm that precision warfare was supposed to prevent.

The Intelligence Problem

Even perfect weapons cannot compensate for imperfect information. Precision-guided munitions hit their designated coordinates with remarkable consistency — but those coordinates are only as good as the intelligence providing them. One USAF officer notes that “the term ‘precision’ does not imply, as one might assume, accuracy. Instead, the word precision exclusively pertains to a discriminate targeting process.”

This distinction matters profoundly. Military spokespeople describe “precision strikes” knowing that civilian audiences will interpret this as “accurate strikes” — a deliberate misunderstanding military force have little incentive to correct. Yet targeting failures remain common: the 2015 Kunduz hospital strike that killed 42 people, the 1999 Chinese embassy bombing in Belgrade, repeated incidents of strikes on Afghan weddings and Iraqi civilian gatherings.

The Hidden Costs

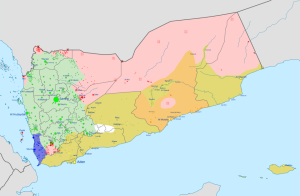

The gap between precision warfare rhetoric and empirical evidence manifests in sobering statistics. Between 2002 and 2020, U.S. strikes in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen killed between 10,000 and 17,000 people — with 800 to 1,750 confirmed civilians among the dead. More recently, drone strikes across six African countries killed over 943 civilians in just three years — casualties that governments either disputed or attributed to “terrorists.”

These figures understate the full toll. Collateral damage — the antiseptic military euphemism for dead civilians and destroyed homes — extends beyond immediate blast effects. Infrastructure destruction cascades into humanitarian crises: a “precision strike” on a power station is “surgical” in execution but indiscriminate in consequence when hospitals lose electricity, water treatment fails, and disease epidemics follow.

Environmental and Technical Realities

The technology itself faces inherent limitations that military public relations rarely acknowledge. GPS-guided munitions are vulnerable to electronic warfare—jamming and spoofing that can render satellite guidance useless. Laser-guided weapons struggle in adverse weather, smoke, and dust—precisely the conditions created by ongoing combat operations. An Australian military study found that 45.5% of laser-guided weapons used in early Desert Storm operations missed their targets due to weather, technical malfunction, or pilot error — hardly the “near-unerring accuracy” promised by manufacturers.

Moving targets compound these challenges exponentially. While military marketing showcases successful strikes against vehicles, such footage represents carefully selected successes, not typical outcomes. The failure rate for strikes against mobile targets remains classified, a telling omission.

The Attrition Reality

Perhaps most damning for precision warfare theory: history provides no clear example of precision strikes hastening wars to swift conclusion. Instead, conflicts like Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and now Ukraine demonstrate that precision-capable forces still find themselves mired in grinding wars of attrition. When strikes prove accurate but ineffective, belligerents escalate to saturation bombardment — the very approach precision warfare was meant to supersede.

The U.S. military now formally institutionalizes procedures for civilian harm mitigation, acknowledging what operational reality has long demonstrated: even with advanced technology and genuine efforts to minimize casualties, modern warfare remains fundamentally destructive. Recent policy shifts — including the 2025 dismantling of offices dedicated to addressing civilian harm — suggest this institutional knowledge remains fragile and subject to always shifting political winds.

Beyond the Mythology

None of this argues that precision-guided munitions offer no improvement over unguided ordnance. They do, significantly. The problem lies not with the technology but with the mythology surrounding it — the dangerous fiction that modern militaries can wage “antiseptic” wars where force is applied with surgical precision at minimal cost.

This mythology serves multiple audiences. It reassures domestic populations that their military operates with restraint and discrimination. It provides political cover for interventions that might otherwise face stronger opposition. It allows defense planners to minimize discussions of civilian casualties by framing them as aberrations rather than inevitable consequences.

But for those living beneath the drones and missiles, the distinction between precise and imprecise warfare often proves academic. The “smart bomb” that destroys a wedding party because faulty intelligence identified it as a terrorist gathering is no less devastating than a “dumb bomb” that misses its military target. The family killed when an accurate strike proves ineffective and requires three follow-up missions experiences no comfort from knowing that each bomb hit exactly where planners intended.

The path forward requires abandoning comfortable fictions in favor of uncomfortable truths. Precision-guided munitions are powerful tools, but they remain tools of war — and war remains, as it has always been, inherently destructive and unpredictable. Acknowledging this reality doesn’t diminish efforts to minimize harm; it makes those efforts more credible and more effective by grounding them in operational truth rather than technological fantasy.

Until military and political leaders stop marketing “surgical strikes” and start acknowledging the messy, costly reality of modern warfare, the gap between precision rhetoric and bloody fact will continue to undermine both strategic effectiveness and moral credibility.

To restate what should be the obvious, war is inherently destructive; it always has been, and always will be. Sometimes, war is a necessary evil…

…Because sometimes, “peace” is merely another word for “surrender”.