An Introduction to Naval Warfare

A few years ago, a United States Navy Carrier Battle Group was implied to have been deployed to the waters off North Korea, amid increasing regional tensions. But — what, exactly, is a “carrier battle group“? For that matter, what is a ‘navy‘?

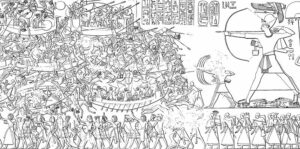

Warfare at sea has been recorded for at least three thousand years, but fighting on the ocean almost certainly occurred long before Ramses fought his desperate battle. As on land, there are a dizzying array of reasons why a nation may fight on the water. However, the challenges of fighting at sea are vastly more complex and expensive than fighting on land, or even in the air. Only the concept of space-based warfare is more expensive.

Like land warfare, naval warfare has tenets and goals. Those are, however, vastly different from those of land warfare. Central to that concept, is the definition of a “warship“. While people usually have some idea of what a “warship” is, that definition is usually shaped by modern entertainment media. A warship, at its core, has two defining characteristics: it is simultaneously, any water vessel that is armed – whether that ship is a bass boat or a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier – and conveys the perception of being under the control of a crew that adheres to both military discipline and a “legal” higher authority. This last, is what separates “pirate ships” from “naval vessels”.

Broadly speaking, there are three basic kinds of naval forces. Sometimes, there may be aircraft of various type associated to each force; there may be marines/’naval infantry’ (ground troops attached to the naval force) and there may be some form of “special operations forces” as well. The three basic types of forces we will briefly examine here are categorized as “blue water“, “green water“, and “brown water“.

First, however, we need to address the two basic schools of thought, regarding naval warfare.

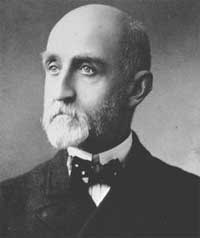

Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, USN (1840-1914), was called “the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century” by British historian Sir John Keegan, OBE, FRSL. Mahan’s seminal work, “The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 (1890)“, and its sequel, “The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793-1812 (1892)“, defined naval theory at the end of the 19th Century, and helped encourage the destructively expensive naval arms races of the early 20th Century.

Mahan’s central theory argued that control of the sea was vital to a nation’s greatness, and that a navy’s main focus should be on controlling the seas by destroying an enemy nation’s main fleet at the earliest stage of war possible, instead of worrying about a more nuanced approach.

The naval aspect of World War 1 was inconclusive as to whether Mahan’s theory was correct or not, as there were few fleet actions, and those few were inconclusive draws. However, Mahan formed the basis of both Imperial Japan’s, and the United States’ naval doctrine in World War 2. For the Japanese, Mahan formed the core of their doctrine against Imperial Russia in the Russo-Japanese War, resulting in the decisive fleet action at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905.

However, Mahan’s theories were not foolproof. In fact, they masked serious problems.

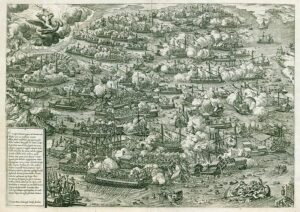

The Japanese were never able to force a decisive main fleet surface action on the US Navy in World War 2. Likewise, the US Navy, as a result of losing its “battleship line” on December 7, 1941, as well as the disasters of the Java Sea and Savo Island – among other – was forced to abandon their Mahanian plan to find and destroy Japan’s main battle fleet in a titanic gun battle, in favor of limited raids with aircraft carriers. In fact, when the decisive battles did come, none of the warships involved came close to being within sight of each other.

Corbett’s Balanced Approach

Sir Julian Corbett came to naval strategy as a civilian, in mid-life. Already a well-regarded historian, Corbett made friends in the Royal Navy with his more limited and nuanced approach to naval strategy, which offered a more realistic application of naval power projection that suited Britain’s needs as an Imperial power, even in its waning days. While agreeing with Mahan about the importance of sea power to a nation, Corbett took a completely opposite view of how to maintain this, arguing that control of the sea did not necessarily have to depend on smashing the main enemy fleet. He went further, arguing that “control of the seas” could be maintained if the fleet could ensure the security of the nation’s maritime commerce while inhibiting, if not outright halting, that of the enemy. German Grand Admiral and Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office Alfred von Tirpitz, dismissed any sort of “commerce raiding” naval strategy (Corbett’s main view, in its most basic form) during World War 1, opting to do his best to use Mahan’s theories against Britain.

By 1945, it was clear that Corbett was the more correct of the two theorists.

Very briefly, a nation’s “fleet” is the total number of warships it has in current service, along with such vessels it might have “in reserve“, which can be quickly brought into service. For some time, during the late-19th Century, there was an idea that a nation’s “fleet” consisted of all of its major ships, operating en masse, in accordance with Mahanian principles.

The United Kingdom largely attempted to adopt this strategy, keeping the bulk of its main battle fleet massed in British home waters, while dispersing a mush smaller portion of its fleet to stations around the world. The United States, however, faced the harsh reality that due to its geography, it would be forced to split its fleet in any major conflict involving a war in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. This was proven true in 1941, as the USN was forced to fight in both oceans, simultaneously.

What everyone generally thinks of when hearing the word “navy”, blue water forces focus on three basic missions: projecting national power well beyond the shores of the home nation, defeating enemy fleets, and “maintaining the SLOC.”

The ‘SLOC‘, or ‘Sea Lines Of Communication‘, are the maritime conduits through which food,

fuel, raw materials and finished goods flow. Very few countries are truly self-sufficient, and a nation under attack has a desperate and immediate need to keep the sea open to merchant vessels funneling supplies to them. It was for this reason that winning the Battle of the Atlantic was so vital to the Allied war effort, because losing it would have forced Britain to surrender; world history would have been fundamentally different had that occurred.

Conversely, Imperial Japan’s failure to secure its own vital maritime conduits guaranteed its defeat. Already vastly overmatched by the United States in the industrial and economic arenas, as well as tying down vast amounts of resources promoting its attempted conquest of China, the Empire’s forces were slowly strangled, as US submarines eventually operated with near impunity. It can be truthfully alleged, that the promise of unrestriced submarine warfare was realized not by German Kriegsmarine’s U-Boats, but by the US Navy, as its submarines sank at least 55% of Japan’s merchant marine losses during the war.

While there have been very few naval battles, as such, in the modern era (and haven’t been since the end of the Napoleonic Period), projecting power is still necessary, as was recently demonstrated by the international anti-piracy patrol off the Horn of Africa, and most famously, by the frequent deployments of the US Navy throughout the world — parking a carrier battle group – containing more fighting power on its own, than the total combat power of most national armed forces…before adding the potential of several thousand US Marines to the mix – off the coast of a restive country is a serious statement, sufficient to give all but the most delusional leader and their supporters serious pause.

While the USN is the only navy currently capable of doing this on any large scale, other countries such as Britain, France and India can deploy smaller but still very powerful forces to trouble spots, actual and potential. The Chinese “People’s Liberation Army Navy“, while large, is not well-practiced in “expeditionary operations“, as yet, and – despite certain breathless reporting – has yet to demonstrate more than a rudimentary capability.

However, while some seventy percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, the remaining thirty percent is land. This may seem like a throwaway statement, but according to the United Nations, an estimated 60% of the Earth’s population live within 100km (62 miles) of an ocean coastline…it is for this very reason, that the United States maintains the largest “naval infantry” force in the world. While marine units are certainly capable (or should be) of seizing a section of hostile shore or a port area, their primary function is to hold that space just long enough for reinforcments to be landed, or some other limited mission completed. This is because – in a similar manner to airborne forces – most naval landing forces (short of a massive assault landing, such as D-Day or Okinawa) are very light in combat power, relying far more on confusion, fear and intimidation…which only works for a short time.

Green Water operations – taking their name from the shift in color from the deep blue of the open ocean to the “sea green” of coastal regions – primarily involve either getting troops ashore (“over the beach“), or finding and suppressing coastal anti-ship defenses, whether troops are going to be landed or not. It is here, that most naval mines are laid, to restrict access to vital coastal regions. This is also where most “coast guards” operate, whether under wartime missions, or during peacetime, conducting customs and safety inspections, police functions, and the occasional search and rescue operation.

In general, green water fleets are small in total hull numbers, as well as overall tonnage, but their functions are, comparatively, much more complex than those of blue water fleets. However, because the ships are orders of magnitude less expensive – at least, for the strictly defensive functions – this is what most navies in the world are composed of.

Humankind’s first water forces were riverine – they operated on those rivers deep enough to take hulls carrying significant numbers of occupants. In a word, those ships were able to carry enough people to both operate the boat, and fight from it.

Riverine warfare involves the control of waterways away from the ocean shore. Any waterway – natural or man-made – that can be used as a highway to transport people and goods, is a vital conduit for a nation. Good examples are major rivers, such as the Mississippi, the Rhine, the Amazon, the Nile and the Mekong; the list can continue, running into several pages.

Ships operating in rivers and delta’s are almost always significantly different in design from their sea-going cousins, but are no less deadly. It is here, where many countries first “dip their toes“, so to speak, in nautical operations. Speeds in rivers and estuaries are generally slower, as is the draft the ships must deal with.

The vessels used in riverine operations can range from shallow-draft, high-speed boats – including small high-speed craft, with a machine gun mount bolted on – to large-scale, heavily-armed, river monitors. These ships are capable of both direct fire as well as indirect fire support missions, forcing enemies ashore to consider their distance to waterways, as well as roads.

Naval Special Forces

Above, we briefly touched on marines/naval infantry. Here, even more briefly, we will touch on naval special operations forces.

The idea of non-marine special operations forces, while not new, has never before reached a level comparable to that of today. This is largely driven by technology, but parochialism also plays a role.

Modern naval special forces grew out of three varied strains from World War 2: Italian Navy commandos operating in the Mediterranean; British Royal Navy commandos operating in the North Sea, the Atlantic, and in the Pacific; and US Navy “frogmen” operating mostly in the Pacific. In general, these operations fell into three categories: reconnaissance (especially beach reconnaissance); sabotage; and supporting intelligence operations via the insertion and extraction of agents.

Like all special operations forces, however, these forces are difficult to employ to their full potential. Their training – of necessity, long and arduous…and expensive – means that they are extremely susceptible to poorly-thought out missions. The numbers of politicians capable of understanding how and when special forces in generally – and naval special forces in particular – should be deployed, is thin indeed.

Conclusion

Naval forces are generally the most expensive sector of a nation’s armed forces. Purpose-built warships represent a very significant investment for any nation, even (perhaps especially) the United States. It is also easy to forget, amid a slew of video games where real people do not die, that even the smallest modern destroyer carries a crew of well over one hundred people…and potentially a crew of thousands.

Anyone talking about naval policy needs to keep that foremost in their minds.