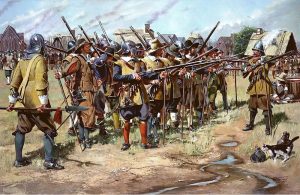

War is hard. That is an oft-repeated phrase, but it is nonetheless true. People are trying to do violence to you, and to those around you…and frequently, it doesn’t matter if you are wearing a uniform or carrying a weapon or not. There are loud and scary noises, a lot of dirt, mud and bugs (among other unpleasant things), and people screaming in fear. And then, it starts raining…or hailing…or snowing. These things combine to make your life infinitely more miserable and terrifying than it already is.

But – the above are personal things. What about the wider context?

Last week, we discussed the effects of volcanic eruptions on logistics, the field of supplying armed forces. Here, we will look at the wider effects of weather on military operations.

Wars and the battles they are composed of are directly impacted by the weather. Armies, air forces and navies are all at the mercy of the weather. While unexpected “snow days” for civilians may mean an inconvenience in getting to work, and while a levee being breached by heavy rain can be a disaster that destroys towns and homes, for armed forces these events can be catastrophic when they happen unexpectedly. Weather forecasting is so vital to military forces, that multiple manuals are now devoted to it.

Militaries have known this for centuries. But, is in only in roughly the last two hundred years that militaries began to seriously monitor weather conditions across the wider “operational region” versus simply the local battlefield. Indeed, until 1950, meteorologists were not permitted to so much as say the word “tornado”, much less try to predict them before they formed, as this was essentially “career suicide”.

The US Army would not form a weather forecasting service until 1870, with the US Navy joining the program in 1873. The British were no better, not founding a meteorological office until 1854. This very late development was due to the belief dating from at least the Middle Ages that attempting to forecast the weather in any way was a form of witchcraft.

This frequently hamstrung military operations, sometimes in catastrophic ways; Napoleon and Hitler come to mind immediately.

In the context of combat operations, rain is bad, because most land operations are prosecuted off of prepared roads; “cross-country” is the word of the day. Heavy rains will turn normally solid fields into mud pits, quagmires that will swallow vehicles and troops. This is especially true when levees and dams are deliberately destroyed, aside from the sheer destruction inflicted on civilians, and the infrastructure to support them, in the combat area. This us, in fact, the accusation leveled at Russia in June of 2023, when the Kakhovka Dam in the Kherson Oblast of Ukraine was breached and flooded the area.

For air forces, severe weather simply grounds flights. But, those force’s airfields are not immune from damage. Clark Air Base, long a center of US military operations in the Far East, was functionally destroyed by the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991.

And neither are naval forces immune. The US Navy maintains a policy of sortieing its ships and aircraft away from port areas threatened by large storms, lest they be wrecked by the storm’s surge and wind effects. And with good reason – although dangerous, getting ships out of port as quickly as possible is usually the safest option…but not always.

In 1944, during WW2 combat operations in the Pacific, the US Navy’s Task Force 38 was struck by a massive typhoon that nudged the scale as a Force Five hurricane on the modern scale, similar to Hurricanes Katrina and Andrew. The storm actually sank three destroyers, damaged nine more warships and killed nearly eight hundred sailors.

And, as both Napoleon and Hitler discovered, snow is a terrible force, occasionally freezing troops to death on vast scales. Snow is like rain, but worse. Some forces can thrive in snowy and icy environments, but most people – and troops – cannot.

And weather is not limited to hurricanes, ice, or rain. In 2003, as US and Coalition forces advanced north towards Baghdad, they were struck by a massive sandstorm that forced the advancing columns to halt, because visibility was reduced to zero.

Planning military operations on a board game is easy. Doing it in real life is seriously hard work. It is only “witchcraft” to the mentally dense.

To quote the great Chinese general, Sun Tzu: