Almost a year ago, we briefly discussed the common hand grenades used by infantry and police around the world. These remain among the most common non-rifle weapons carried by soldiers around the world. While we have touched on this particular subject in passing in several articles, this week we are looking at the hand grenade’s ‘next level’: the Rifle Grenade.

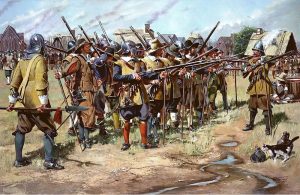

Since grenades came into widespread use in the mid-17th century, the weapon’s greatest detraction was its range. Limited to the strength and coordination of the thrower, hand grenades can only be used at very short ranges, typically within 50 yards/45 meters, at the most extreme range. While it is technically possible to throw a hand grenade farther, outside factors – extreme fear, fatigue, enemy fire, etc. – severely limit the throw range.

Coupled to this, in the early days, fuses were generally a piece of rope that had been soaked in a solution of saltpeter (KNO3) or gunpowder. Obviously, this did not make for a very reliable timing system in the field, where it was openly exposed to rain and mud…and other fluids. As a result, grenades faded from use in 1760’s, their memory kept alive by the units of European armies specially selected for use – the Grenadiers – who, due to their size and strength (the better, it was believed, to throw grenades farther) were converted into assault units, designated to assault an enemy position.

As World War 1 dawned, technology had advanced to the point where reliable timing fuses, protected from the environment, finally made hand grenades reliable enough to use; tactics, however, still had to catch up, as in 1900 the term “rifle company” meant precisely that – 100-120 men, equipped with rifles and bayonets, with only officers carrying pistols. New, and very expensive weapons like machine guns were actually considered to be light artillery (as their size and weight placed them on light carriages based on those for light cannons and howitzers). They and their heavier counterparts had to be assigned to an infantry unit separately. The PBI’s (“Poor, Bloody Infantry”) had to make do, and figure it out, otherwise.

But, as the horrors of full-scale trench warfare closed in along the Western Front, armies needed a way for the infantry to attack an entrenched enemy. Grenades were ideal, but they could only be used at very close range, and while the opposing trenches could occasionally get to within 100 yards of each other, that was still too far for the hand-thrown grenade.

The British, German and Austrian solution to the problem was the “rod” grenade. This worked exactly how it sounds: a steel rod was attached to the bottom of a hand grenade that had been fitted with a longer fuse; the rod was inserted into the rifle’s muzzle and aimed, then the grenade’s safety ring was pulled out, and the grenadier pulled the trigger to fire a blank cartridge with no bullet in the case. The force of the gases from the firing shoved the grenade and its rod out of the rifle, and threw it 150-200 yards or so.

I can hear the groans and shrieks of terror and horror from all the shooters reading this from here.

The rod grenade – while it did work – severely damaged rifle barrels, to the point where a rifle would quickly become useless for anything else, as the stress of repeated firings warped the rifle barrels to the point where they could no longer fire accurately…assuming that they did not blow up in the firer’s face on the next launch.

In response, the British swiftly developed the “cup discharger”. This was a steel cup, just large enough to fit a hand grenade inside, that was clamped onto the muzzle of the rifle. A blank cartridge was loaded, and a hand grenade with a “gas check” plate welded to its bottom was slipped into the cup, and fired. While this system still placed heavy stress on the barrel from gas over-pressure, it was nowhere near as bad as the rods had been. Great Britain would continue to use this system through World War 2. Both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan would use a similar system, although both of those combatants used rifled dischargers to add range and accuracy.

The French tackled the problem in a very…well, ‘French’ manner, with the “VB” grenade, named for its designers, Messer’s Viven and Bessières. This also used a special cup – in this case more like a cylinder, which clamped to the rifle’s muzzle. A specially designed grenade (quite different from a standard hand grenade) was slipped into the cup and aimed. The grenadier did not have to use a special blank round, though – the VB was activated and launched with a conventional bullet: When fired, the bullet exited the muzzle, deftly striking a lever inside the grenade, which activated the percussion cap to ignite the fuse. The action of the lever’s bottom end swing closed trapped the propellant gases coming up behind the bullet, and used them to throw the grenade clear of the discharger cup.

The VB worked very well, and solved the only real problem of the cup discharger, in dispensing with the blank cartridge. When the United States entered the war it, too, adopted the VB design, although it had to manufacture its own weapons, as American and French system and calibers were significantly different. The US would retain the VB design until the early stages of World War 2, using them as late as the 1942 Battle of Guadalcanal. In contrast, while the French military abandoned the VB after World War 2, their Gendarmerie would use the design to launch tear gas grenades into the 1990’s.

World War 2 Japan took a very different course, with their Type 100 Grenade Discharger. This device fired standard hand grenades from a cup fitted to the rifle muzzle, and that was launched using a standard rifle bullet. However, unlike the VB system, the Type 100 was offset from the muzzle, and used a gas tap from the firing to launch the grenade out to about 100 yards. This is not surprising, however, if one knows the history of Japan’s infamous “knee mortar”.

The United States led the way after World War 2, by adopting the “spigot” type of rifle grenade. This mounted a grenade on top of a tube with stabilizing fins, which slipped over the muzzle of the rifle, and was fired by a blank cartridge. This eliminated the need for a separate launcher, although still requiring a special cartridge. NATO would eventually standardize on a grenade with a mounting tube with an internal diameter of 22mm. This allows a common system for any standardized rifle to fire both blank cartridge, “shoot-through”/VB-type grenade and “bullet-trap” type grenades.

Advancements in materials technology would lead to the development of the “bullet-trap” design, allowing a rifle to fire a grenade with a regular cartridge; the rifle bullet would be captured by the bullet-trap on the grenade, using both the force of the cartridge’s gas and the physical force of the projectile’s impact to launch the grenade.

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, with the rise of the “intermediate cartridge”, the muzzle-launched rifle grenade began to fall out of favor, as the intermediate cartridges available lacked the energy to effectively launch the older grenades to the same ranges. The only solution was to shrink the size of the grenades. This led to rifle grenades being seen to be less effective than lightweight rocket launchers such as the M72 LAW. There was, however, a replacement that stepped in and took over: the 40mm Hi-Low Grenade.

First deployed by the United States in 1961 with the adoption of the M79 grenade launcher and the later M203 system that could be easily mounted under the barrel of most military rifles, this system was so revolutionary, no established state military’s land warfare units lack some system firing a variation of the Hi-Low system.

These weapons are able to launch grenades out to 200 to 400 yards (sometimes farther), which have a blast effect similar to a regular hand grenade, but that also fire a wider variety of grenades than the older models of rifle grenades.

Wars are always violent; expecting them to be “clean” or “surgical” is a fantasy. Weapons development is not evil, if the weapons make your forces more capable of ending a war faster, with as little destruction and savagery as possible.

As the legendary Chinese general Sun Tzu said in the opening lines of his military treatise, The Art of War, in c.500BC –

The art of war is of vital importance to the state.

It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence under no circumstances can it be neglected.